INTRODUCTION

"I have a future leader in my church who is interested in taking the next step towards ministry. I don’t have much experience training others. What advice can you give us?"

This paper represents our considered response to common questions that we are asked about effective training and development, like the question above. It aims to serve a wide range of leaders in church and parachurch ministries in Australia and overseas. It begins by identifying five common training strategies adopted by churches. It outlines a research-informed process to select the most appropriate training strategy and program for a particular context based on two critical questions: 1) what impact will it have on leader development?; and 2) how difficult will it be to implement?. It then organises this material into an integrated framework for effective training and development.

We have provided three appendices containing further explanations and illustrative examples of key concepts from our context of Reformed and Presbyterian pastoral ministry in Sydney, Australia. We believe this additional detail will help pastoral leaders and future leaders from a range of denominational backgrounds, ministry contexts and geographical settings understand the practical implications of our recommended process. It should also equip them to answer many of their own questions about training and development.

We are not aware of a similar paper aimed at pastoral leaders (ministers and elders) and future leaders (less experienced leaders) that attempts to integrate research-based insights about training and development from multiple literatures into a sensible decision-making process and integrated developmental framework. We pray that this material serves others inside and outside our defined context, and that it provides a platform for more rigorous and intentional conversations about raising the next generation of pastoral leaders.

COMMON TRAINING STRATEGIES

Pastoral leaders in our theological tradition and wider Evangelical culture tend to adopt one of five training strategies for future leaders in their church or parachurch ministry:

-

Neglect

-

Student pastor

-

Internship

-

Apprenticeship

-

Traineeship

Neglect is a common response to training future leaders, though it is seldom chosen deliberately. Neglect occurs when future leaders are not identified and/or given opportunities for training and development. It is the default strategy when no other training strategy is selected.

A student pastor strategy involves pastoral leaders engaging a seminary or theological college student in a part-time assistant role. This role could be paid or voluntary. This strategy has a long history, takes many forms, and is relatively common among future leaders participating in full- or part-time theological study, especially as they near the end of their studies.

An internship is a training strategy modelled on university-workplace internships that sits in a similar space to the student pastor strategy. These strategies are normally overseen by a university or college. They are designed to give approved students the opportunity to acquire relevant learning experiences in the field, under the supervision of approved coaches, in ways that connect with their university or college studies. Christ College was one of the first to develop a structured three-year internship that integrates field and classroom learning as part of a degree-level qualification for pastoral leaders and deaconesses seeking ordination. Other seminaries and theological colleges have begun developing their own internship strategies.

An apprenticeship is a training strategy that is traditionally used to prepare school leavers for working in trades that involve manual labour. Apprenticeships are full-time paid roles that last three to four years during which apprentices receive on-the-job training from an employer. They also undertake part-time training towards an industry-recognised qualification that prepares and authorises them as a qualified tradesperson.

In Australia, this apprenticeship strategy was reconfigured in the early 1980s to provide paid ministry training opportunities for university graduates and younger workers under approved trainers. They are commonly implemented in churches and university campus ministries over a two-year period. Unlike a traditional apprenticeship strategy, part-time training towards an industry qualification is not required. Many, but not all apprentices, defer their study at a seminary or theological college until after the completion of their apprenticeship. Finally, instead of being paid a wage by their employer, apprentices raise their own funds in partnership with their church and/or parachurch ministry, family and friends. Most apprenticeships are offered in partnership with specialist parachurch organisations like MTS (Ministry Training Strategy) who can provide a broad training framework/curriculum, training resources, and tax-deductible fundraising infrastructure. Apprenticeship strategies are also developed independently by churches and parachurch organisations and therefore take many forms.

A traineeship is a training strategy found across many service industries. Like a traditional apprenticeship, trainees receive a salary from their employer and on-the-job training. They also complete a part-time industry-recognised qualification that prepares and authorises them for relevant work in their industry.

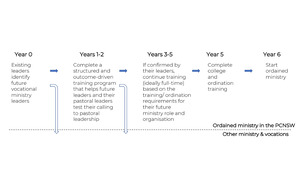

Some traineeships offered by churches and parachurch organisations in Australia are little more than apprenticeship strategies by a different name. Christ College created a new kind of traineeship that combines key elements of apprenticeship, internship and traditional traineeship strategies. Like an apprenticeship, trainees make a full-time commitment over two years to serve and undertake on-the-job training under an approved coach in a ministry context. They are supported financially by various partners and tax-deductible fundraising infrastructure. Like an internship, the Traineeship is overseen by the college and is structured into a comprehensive range of field and classroom learning experiences. And like a traditional traineeship strategy, trainees complete an industry-recognised award[1] part-time. The Traineeship is aligned with ordination training required by the Presbyterian Church of Australia. This enables those who complete the Traineeship to receive credit for the full first year of the required training that prepares and authorises ministers and deaconesses for work in this context. We are not aware of other seminaries, theological colleges, churches or parachurch organisations that have developed a traineeship strategy like this.

The two most critical questions that pastoral leaders and future leaders should ask in relation to any training strategy are:

-

What impact will it have on leader development?

-

How difficult will it be to implement?

Variations of these questions are used in the lean management literature to analyse and select strategies.[2] The preferred strategies are generally high in impact with relatively low difficulty to implement. These questions are explored further in the following sections of this paper.

IMPACT ON LEADER DEVELOPMENT

The impact on leader development refers to the estimated value or benefit of the training strategy on the development of the future leader.[3] Therefore to understand how leader development is impacted, it is important to identify the factors that influence said development.

Leader development is defined as the capacity of individuals to be effective in leadership roles and processes.[4] Leader development is distinguished from leader training. Training is focused on offering proven solutions to known problems, such as the teaching of particular techniques. Development, by contrast, focuses on building individual capabilities,[5] especially the capacity to meet unforeseen challenges.[6] It has been argued that the failure to recognise this distinction between development and mere training lies behind the poor outcomes of many leader development programs.[7]

Leader development takes place on three different levels. Like an iceberg submerged in the sea, some developmental changes are easier to perceive than others. At the surface level are observable skills and behaviours[8] such as teaching and leading others. These are enabled at the meso level by less-observable processes of self-regulation[9] and leader identity formation.[10] A common example for many pastoral leaders is discerning a ‘technical call’[11] to serve as an ‘officer’ in Christ’s church.[12] At the foundation level are invisible adult development processes[13] like character formation that build on a moral/ethical foundation.[14] The scope of leader development is therefore as broad as our “life and doctrine” (1 Tim 4:16).

There can be significant variation in the leader development outcomes across and within training strategies. This variation represents a major risk that should be evaluated before selecting the training strategy.

We have distilled what we believe are the most significant influences on leader development outcomes into three distinct categories:

-

Alignment with stakeholder interests

-

Coherence of program design

-

Consistency of leader development outcomes

We recommend strongly that pastoral leaders and future leaders adopt these categories as lenses to evaluate the relative merits of different relevant training strategies before making a decision to pursue a particular strategy.

1. Alignment with Stakeholder Interests

The first and most important category is stakeholder interests. Most frameworks in the training and development literature begin at a similar point but refer to these concerns as ‘needs analysis’.[15] We prefer the language of interests rather than needs, as it captures a wider range of relevant concerns that can influence the outcomes of different training strategies.

Stakeholders are those who are likely to be affected by the training strategy and who can influence the outcomes of it.[16] The most influential stakeholders are those with both a high level of interest in the training strategy, and a high degree of power or influence to “make or break” the change.[17] Stakeholder interests refer to “specific priority preferences at a given time”.[18] They are the things that stakeholders care about most that drive their emotions, motivations and actions.[19]

Stakeholder Levels

It is recommended that stakeholder interest analysis take place at three concurrent levels: mega (societal), macro (organisational),[20] and micro (individual).[21] If pastoral leaders want to make an impact beyond the macro level, they should begin with analysis at the mega level,[22] especially if these interests can impact upon the viability and effectiveness of the training strategy.[23]

A pastoral leader and future leader in a local church are likely to find the following stakeholders to be the most significant:

-

Denomination/network (mega)

-

Elders/staff (macro)

-

Future leader (micro)

Other stakeholders could also be considered at each level. The potential significance of these stakeholders will depend on the extent of their interest in, and influence over, different training strategy choices in their particular context.

Interest Categories

We have observed several common categories of stakeholder interests in relation to training strategies for pastoral leaders and future leaders.[24] Many of these categories operate concurrently at the mega, macro and micro levels. These categories include:

-

Aspirations – vision, calling, hope, goal/s or desired outcomes

-

Role capabilities – relevant attributes, competencies or qualities required to perform effectively in a given role

-

Ministry context/polity – distinctive aspects of the setting where the role is performed, such as culture, geography, organisational structure and critical challenges

-

Confession/convictions – the approved confession of faith and relevant convictions relating to doctrine and ministry practice

-

Regulations – laws and rules that prescribe or limit possible training strategies

-

Resources – various means that enable or limit effective training, such as time, energy, expertise, and funding

For those considering the possibility of pastoral leadership in a local church in Australia, church denominations and ministry networks continue to exert significant influence. Much to the surprise of many future leaders, there are important and particular stakeholder interests across different denominations and non-denominational church networks.[25]

Align Training with Stakeholder Interests

The ideal training strategy for a future leader should align with their stakeholders’ interests, especially their own.[26] Furthermore, careful reflection and the ability to articulate these interests can be advantageous for future leaders before they identify a suitable training strategy.

For example, future leaders interested in ordination in the Anglican Diocese of Sydney must align their training strategy with a number of denominational interests. These include baptism and communicant membership in the Anglican Church of Australia (ministry context/polity), completion of two years of observation and supervision in ministry (role capabilities and requirements), discernment as a candidate for ordination (aspirations, role capabilities and confession/convictions), making Solemn Promises (confession/convictions), and completing required study at Moore Theological College or Youthworks College (regulations).[27] There are similar denominational interests for those interested in ordination with the Christian Reformed Churches of Australia[28] or accreditation with the Baptist Churches of NSW and ACT.[29] Networks like the Fellowship of Independent Evangelical Churches in Australia have their own distinctive aspirations, confession/convictions, polity/governance, regulations and resources.[30] For those interested in serving overseas through a church or parachurch ministry, additional interests should be considered such as those of the partner mission agency.[31] We recognise that there is a possibility that these interests or requirements may be perceived as laborious to some. Yet, we believe that these function like guard rails to clarify and test[32] a future leader’s calling, direct their training pathway in a manner that is doctrinally and historically anchored, and provide the most holistic training possible.

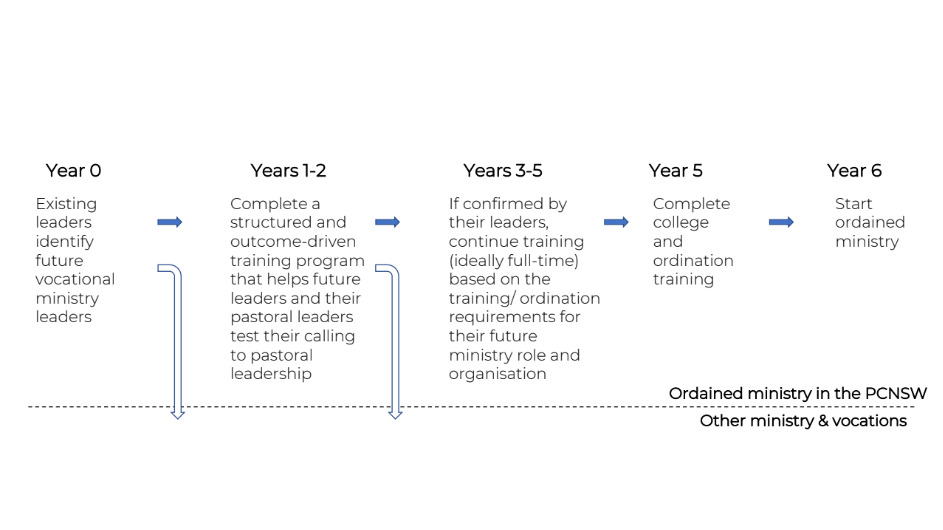

An example of common stakeholder interests for future leaders we have spoken to in our context (the Presbyterian Church of Australia in NSW and the ACT) is outlined in Appendix 1. Our suggestions for clarifying these stakeholder interests, and our recommended training pathways that align mostly closely with these interests, can also be found in Appendix 1.

Our counsel to analyse stakeholder interests prior to selecting the training strategy will appear to be common sense for some, and counter-cultural for others. In our wider church culture, denominational distinctiveness is often smoothed out in favour of a generalised Evangelical identity.[33] As a result, it is not uncommon for us to meet future leaders who aspire to serve as a pastoral leader in our denomination, but failed to investigate their stakeholder interests when they decided on their initial training strategy. We know many future leaders whose training strategy produced a lower than desired impact on their leader development, while simultaneously taking more years to complete at a higher financial cost, compared to other strategies more aligned with their interests. Our hope in raising the issue of stakeholder interests is that it encourages more future leaders and pastoral leaders to ‘look before you leap’ into important training strategy decisions.

2. Coherence of the Program Design

A training strategy alone is not sufficient to deliver leader development outcomes. A particular training program comprised of various elements is also needed to deliver the hoped for outcomes of the training strategy.

We have identified five foundational elements relating to the design of a training program that impact upon the development of a future leader. These elements are:

-

Target audience

-

Program outcomes

-

Development ecosystem

-

Program evaluation

-

Resource management

These elements should cohere and work together. There ought to be ‘constructive alignment’[34] between the learning outcomes, learning activities, and assessment/evaluation within coursework and formal training (see further our discussion of the development ecosystem). This same principle of coherence should also operate at the program-level, across the five elements, as well as any partnerships between training organisations and industry partners[35] like churches. An example of coherent program design drawing on the Christ College Traineeship can be found in Appendix 2.

Target Audience

The training program should have a clearly defined target audience it aims to serve.[36] The target audience in our case should be the future leader being trained.[37] For training to be effective, it must be targeted.[38] A good indication of the targeted nature of the program audience is formal entry criteria that communicates the shape of the target audience and restricts entry to those who don’t meet this criteria.

Program Outcomes

There should be explicit program outcomes that the future leaders who join the training program will attain at the completion of their program. It is recommend that these outcomes are learner- or leader-centred, so it is clear how every leader will benefit personally from participating in the program.[39] This normally means defining outcomes in terms of specific leader capabilities[40] that can be observed and measured.[41] This is in contrast to the practice of stating general program objectives that are not leader-centred,[42] and which may prioritise the objectives of the church or parachurch organisation overseeing the program. The most effective learning and development organisations ‘design the complete experience’ from the participant’s perspective rather than the course perspective.[43] Framing leader-centred program outcomes is also more likely to foster transformational learning and teaching experiences,[44] especially when these outcomes inform the rest of the program design.[45]

Development Ecosystem

Every training program assumes their participants will develop within a particular ecosystem or framework comprising of multiple related influences. Whether this ecosystem is made explicit or not, all the parts within it should cohere or align with the program outcomes to cultivate the specific conditions these leaders will need to develop during the program.

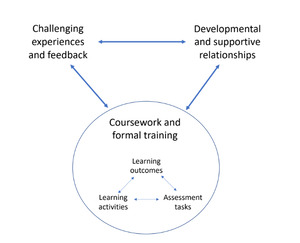

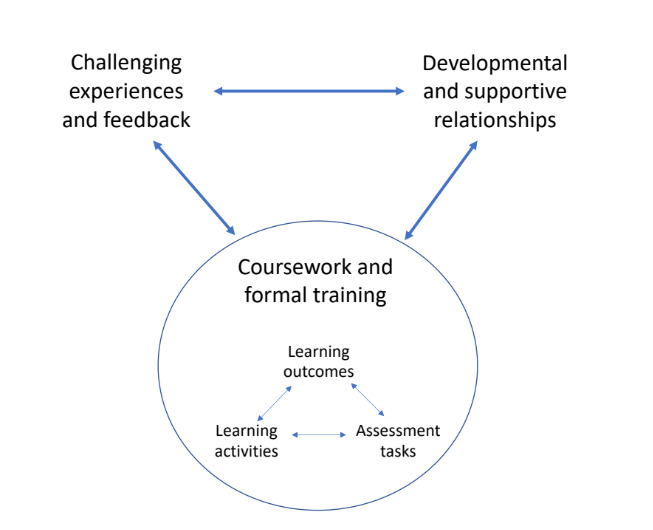

According to the research, leaders need three important and related conditions to develop.[46] For the Christian, these conditions are the ‘means’ or ‘second causes’ that God normally uses in his ordinary providence.[47] These conditions are summarised in Figure 1.

Leaders develop over time through experiences,[48] especially when these experiences challenge leaders to struggle and stretch beyond their current capabilities.[49] Cross-cultural analysis of the events that had the greatest impact on the development of leaders has found that challenging experiences are the most frequently cited factor.[50] Engaging personal experiences were also found to be the most important factor in helping Christians to grow spiritually.[51]

The nature of the challenge can arise for multiple reasons such as novelty, difficult goals/tasks, conflict, dealing with adversity,[52] experience in a new culture, early work experiences, short-term and major projects,[53] promotions and postings.[54] The difficulty of the challenge should not be too great and must be accompanied by appropriate feedback.[55] This feedback can be from the leader themselves or others. Its value is to show leaders where they are now and what they need to develop further.[56] Feedback fosters personal goal-setting, learning, and the development of expertise.[57] When this feedback is positive, it motivates and reinforces desired behaviours.[58]

Leaders need more than just challenging experiences and feedback; they must also be willing to reflect on their experiences,[59] and learn from their experiences.[60] Two different kinds of relationships support this process.

Developmental relationships refer to those people who help the leader learn lessons about leadership. These are transmitted through relational feedback such as coaching, one-to-one mentoring, and forms of peer/group mentoring.[61] These relationships create space for leaders to participate in a transformation process by identifying, sharing and examining points of view that promote insights, understanding and new action.[62] Empirical research among Christians has similarly found a transformation ‘sweet spot’ where ‘truth’ is given by a ‘healthy leader’ to someone in a ‘vulnerable position’.[63]

Supportive relationships enable leaders to experience safety and find a new equilibrium.[64] They also help leaders handle the struggle and bear the weight of the challenging experience and development process.[65] This role is often played by supervisors, co-workers, family and friends.[66]

The third important condition for leaders to develop is coursework and formal training.[67] This includes formal leadership development programs, academic programs, study tours, workshops, and action learning.[68] It also includes training towards industry-recognised awards common to many of the prior discussed training strategies. The critical elements that must be ‘constructively aligned’ for effective coursework and formal training are the learning outcomes, learning activities, and assessment tasks.[69] These three elements should also align with the leader’s experiences and social relationships (especially with superiors).[70] Aligning coursework and formal training with real-life challenges is consistent with how adults learn best.[71]

There are different claims in the training and development literature regarding the relative importance and ideal weightings between these three conditions. A popular framework is the 70/20/10 model[72] that recommends the following split for developing leaders:

- On-the-job experiences (70%)

- Social sources (20%)

- Formal training (10%)

This model rightly highlights the significance of challenging experiences and developmental/ supportive relationships, as discussed earlier. But it should not be cited as authority for prescribing their recommended weightings of these elements in a program’s design, especially the minimising of coursework and formal training. This is because the original research was limited in its focus on executive success, not their full range of jobs and skills.[73] Further, other research has found similar rankings of importance, but varying weightings across cultures[74] and industries.[75] For example, one study found the average split across these categories was 55/25/20, with variation observed across industries and organisations.[76] Finally, there are several industries where learning on-the-job cannot take place without the completion of extensive formal training because of the high risk of errors. Commonly cited examples include surgeons, pilots, and accountants.[77] The same rationale can be applied to other kinds of professionals and knowledge workers, such as school teachers, psychologists, and pastoral leaders.

Program evaluation

The training and development of a leader is not complete until they have been evaluated comprehensively. This evaluation should also cohere with other elements in the development program.[78] The design of this evaluation should take place as early as the analysis of stakeholder interests, and the design of the program outcomes and development ecosystem.[79]

Evaluation serves multiple important purposes. It helps the leader to assess their current capabilities and needs, develop a more complex understanding of themselves, and identify gaps between their current state and desired future state.[80] These gaps provide motivation for learning, growth and change.[81] They provide clues regarding how these gaps might be closed.[82] It helps stakeholders, especially the future leader and pastoral leader, determine whether their investment in the program was ultimately worthwhile.[83] Finally, when the evaluation is well-designed and comprehensive, it increases the likelihood that the development program will achieve a high-quality status.[84]

There is a standout framework for evaluation[85] that is used throughout the training and development industry that identifies four related levels of evaluation:

- Reaction – how do participants respond initially to the training event?

- Learning – do participants develop the intended outcomes during the learning event?

- Behaviour – do participants apply what they learned on the job after the learning event?

- Results – are organisational outcomes occurring as a result of the learning events and their reinforcement?

The first two levels of evaluation take place within the context of the coursework or formal training. The first level (reaction) can be measured through observation and simple surveys. The second level (learning) can be determined through various informal and formal assessments over the designated training period.[86] This is the level at which evaluation normally ends,[87] especially when it is not integrated thoughtfully into the development ecosystem and wider training program.

The biggest challenge in most training programs is the application of learning from the classroom to the field or workplace (behaviour).[88] Research has found that there is a higher probability of learning transfer when participants are supported by superiors and peers,[89] when they perceive their training to be useful or relevant to their workplace needs (reaction), and when they acquire the intended learning outcomes from their training (learning).[90] As argued already, these outcomes are more likely when analysis of stakeholder interests takes place before the training begins so the training program can match the needs of participants.[91]

The transfer of learning to the field or workplace should lead to behavioural changes that can be observed and measured by others. These are the kind and level of program outcomes we recommended earlier.

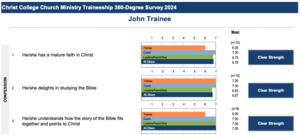

A common approach to determine the extent of leader development over time is a pre- and post-program assessment. These work best when specific outcomes are identified and the same raters are involved each time, a 360 survey is used, or raters are asked to assess change they have observed over time.[92] 360 surveys are particularly effective when they are custom-designed, report credible data, promote accountability through a personal development plan, and involve representatives from across the organisation.[93] If 360 surveys are used, their purpose should be communicated clearly, participants ought to be involved in choosing their raters, and care should be taken to avoid ‘rater fatigue’.[94]

In the training and development industry, it is common for employers funding staff training to identify organisational outcomes they hope to achieve through the training. This is the fourth and final level of evaluation (results). This is less relevant for our purposes, and appears to be less common among churches more generally.[95]

In addition to multi-source leader evaluations like 360 surveys, it is also good practice to draw upon a range of other evaluation data to review the training program itself. This could include surveys and interviews with leader participants and their church-based trainers, assessing program-level outcomes across all participants, and tracking the progress of graduates into the future. As part of this review process, program outcomes should be reported to key stakeholders such as the future leader, their pastoral leader coach, and the relevant denominational committees. This evaluation data can then be used to promote continual improvements over time.

Resource Management

The final foundational element is resource management. The most critical resources are the time, effort, expertise and money of major stakeholders, especially the future leader participating in the training program.

The resources of the future leader should be spent wisely. If a future leader is beginning their ‘journey’ towards ordained pastoral ministry in a particular denomination/network, or the future leader and pastoral leader are seeking to test a potential calling to ordained pastoral ministry in this setting, then their initial training strategy and program should align with this ministry end. It should also align with possible future training strategies and programs, such as required ordination training at an approved seminary or theological college.

In our context, we have observed future leaders and pastoral leaders making decisions to start training programs that took more years to complete, and resulted in inferior leader development outcomes, compared to alternative training programs they could have chosen. We also know of future leaders who completed training programs that required part-time study at a seminary or theological college that was not recognised towards required ordination training in their church denomination. This is poor stewardship of the future leader’s time, talents, and treasures.

The total time and financial cost of completing a particular training ‘pathway’ to vocational ministry should be identified as part of the initial analysis of stakeholder interests. We are aware of some future leaders who did not investigate the total financial cost of their training strategies and later ran out of money to pay for their tuition fees, as a result of tuition fee debt from prior university study. More young leaders in the future are likely to require training strategies that provide tax-deductible financial support from partners to contribute to their living and tuition costs associated with their training strategy.

3. Consistency of Leader Development Outcomes

There are another set of important considerations relating to the consistency of the promised leader development outcomes. In our context, apprenticeship and student pastor strategies have impacted positively on the development of many leaders. However, based on our experiences and observations of many apprentices and student pastors, they do not consistently produce positive development outcomes. Variations in development outcomes represent a significant risk that should be considered before making a decision about a training strategy or related program. We have identified four factors that increase the consistency of leader development outcomes. Examples of these factors from the Christ College Traineeship can be found in Appendix 3.

Program Governance

It needs to be clear who is responsible for overseeing the program and all its elements. For internships, it is recommended that the university or college oversee the content[96] and integration of the internship,[97] such as the linking of workplace tasks with theoretical knowledge delivered in the classroom.[98] For programs based wholly in the local church, oversight will normally reside with the elders or church governance team, even if outside teachers are engaged.[99] For leader development programs with developmental experiences taking place outside the local church, there are likely to be other parties delivering significant parts of the program. Oversight of the program and all development experiences should be assigned to one party who has the authority to make binding decisions in relation to the program and those who participate in, or contribute, to the program. The work of this group could be aided by a governing or advisory board made up of academics/trainers and practitioners/pastoral leaders.[100] This important condition enables the possibility of difficult and ongoing changes to be made that can improve the development experiences of future leaders, as well as addressing the interests of other significant stakeholders.

Common Structure

The adoption of a common program structure improves the consistency of leader development outcomes over time. Research on apprenticeships has found that programs that promote “individualised curricula”[101] can fail to develop common and basic skills that apprentices require in order to work effectively in other contexts after their apprenticeship,[102] also known as “labour market integration and mobility”.[103] When this occurs in an internship or student pastor strategy, especially as part of required ordination training, it can result in students graduating from seminary or theological college without all the required attributes for effective pastoral leadership. Programs that are highly customised around particular individuals are also in danger of being abused by workplace supervisors as a “quick-fix solution for short-term recruitment problems”.[104] Alternatively, the research recommends apprenticeships adopt a high level of standardisation in training content and curricula,[105] along with “more academic forms of education that sustain and develop basic skills”.[106] Finally, common pathways for apprentices to pursue higher levels of education and training are also recommended.[107]

We have observed from our experiences that programs with a common and mandatory structure develop their program outcomes more consistently across participants. This limits, without removing entirely, program variation and individual discretion across leaders and delivery locations. By contrast, programs that lack a common and mandatory structure, usually to promote customisation and flexibility around the future leader and/or their coach/trainer, often result in less consistent leader development outcomes over time.

Program Orientation and Resources

Outcome consistency is improved when future leaders and pastoral leaders receive appropriate training that equips them to participate in, and contribute to, the program. This training is ideally provided during an orientation or induction at the beginning of the program.[108] It could also be provided at later dates, as required. Shared training resources provided to future leaders and pastoral leaders, ideally during the program orientation, reduce variation further. These resources could address different aspects of the program, such as expectations for particular program elements, instructions for developing an annual learning contract, training in coaching conversations, instructional content for church-based training between the pastoral leader and future leader, and multi-source evaluation reports like 360 surveys. All of these resources should cohere with the overall program design.

Quality Control

The final element that improves outcome consistency is quality control, such as monitoring and evaluation systems.[109] This is ultimately the responsibility of the group responsible for governing the program. This group should review program evaluation reports regularly, and make necessary changes, to ensure that the outcomes attained by leaders are consistent with the outcomes that were promised.

We have now discussed a range of factors that can impact on leader development outcomes across different training strategies and programs. When these factors are assessed, along with an analysis of the relative difficulty to implement these strategies (discussed next), pastoral leaders and future leaders should have a sound basis for choosing their preferred training strategy and program.

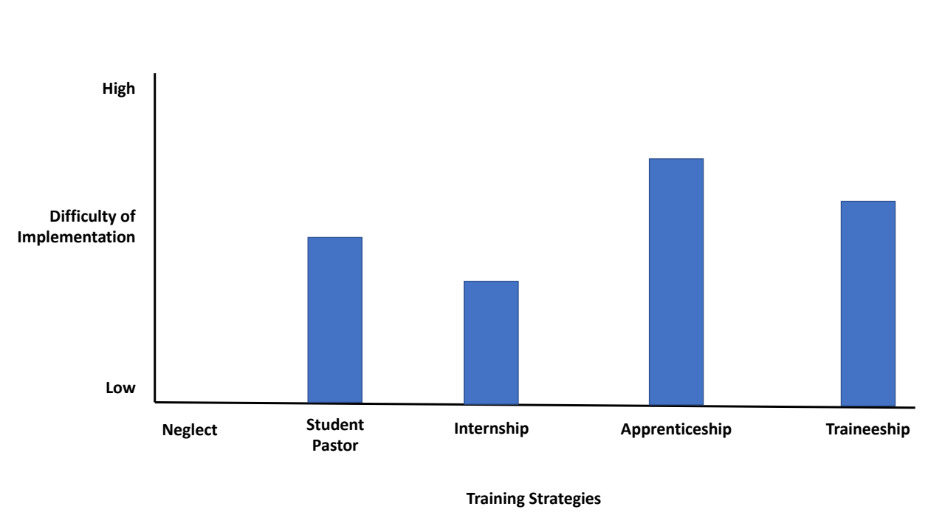

DIFFICULTY OF IMPLEMENTATION

The difficulty of implementation is an important but frequently overlooked issue when evaluating the merits of different training strategies. For our purposes, the difficulty of implementation refers to the time, effort, expertise and financial cost required to implement the chosen strategy.[110] Higher levels of difficulty normally lead to increased costs and risks. Our assessment of the relative difficulty to implement common training strategies is summarised in Figure 2.

The difficulty of implementation increases when pastoral leaders are responsible for training a future leader several days per week (such as an apprenticeship or traineeship strategy) compared to only one or two days (such as a student pastor or internship strategy). This difficulty grows with the range of training elements that the pastoral leader is responsible for coordinating and implementing.

This difficulty can be reduced when important decisions about the design and delivery of the training strategy are made by another party, such as the structuring of a program into common and mandatory core components. It can decrease further when mandatory training and common resources are provided for their use. And it can be reduced again when other parties deliver key elements of the training strategy within carefully pre-defined parameters.

EVALUATION OF COMMON TRAINING STRATEGIES

The evaluation of which training strategy is ‘best’ for a future leader and pastoral leader depends on a number of prior discussed factors relating to impact on leader development and difficulty of implementation. Although the details of these training strategies and related programs will vary within and across other contexts, we can offer some brief comments about the relative merits of these training strategies from our context.

Unsurprisingly, neglect has the lowest positive impact on the development of future leaders. It persists as a common strategy as it is the least difficult to implement.

The student pastor strategy gives the future leader an opportunity to complete a theological education while gaining on-the-job experience concurrently with, but normally independent of, seminary or theological college. In our experience, the impact on future leaders varies considerably. The inconsistency of leader development outcomes from this training strategy was one of the main reasons that Christ College developed its Internship program.

The student pastor strategy normally requires the pastoral leader to develop a role description, gain the support and approval of other church leaders (especially if it involves funding), plan the future leader’s workload, meet frequently with them, and speak to others about them. Some seminaries and theological colleges may provide training and resources for their students and the leaders responsible for them. In most cases however, the responsibility for the student pastor role is in the hands of the pastoral leader.

Since the start of 2019, we have seen positive and consistent leader development outcomes using an internship strategy, especially compared with our previous student pastor strategy. This has been encouraging for us because we believe that the urgency of raising more leaders has to be accompanied by a training strategy that serves and benefits the future leader and their future ministry contexts.

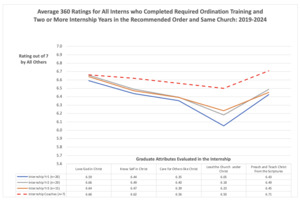

Figure 3 shows the average 360 survey ratings of Christ College Interns who completed required ordination training and two or more years of Internship, in the recommended order, and within the same church.[111] They were evaluated by nine church-based raters[112] across 50 questions that aligned with five of the six graduate attributes or program outcomes for the Course of Training[113] required for ordination. These questions required raters to respond using a 7-point Likert scale of agreement that were coded with a numerical rating from 1 to 7.[114] To assist with the interpretation of this data, the average 360 survey ratings for ordained pastoral leaders serving as approved Internship Coaches are shown in red as an external benchmark.[115] These Coaches were evaluated using the same 360 survey questions and an almost identical methodology[116] as the Interns.

The average ratings for Interns were high across all years, and across all graduate attribute program outcomes, with a range of 6.05 to 6.66 out of 7. These ratings improved across all graduate attributes between the first and second year of the Internship, especially in the category Lead the Church under Christ. The differences between the average scores in the second and third year are marginal and reflect our focus on assuring program outcomes in the final year.

These 360 survey program evaluations were conducted in the same kind of context, and by the same kinds of church members, that these future leaders are likely to serve as ordained ministers as deaconesses. This evaluation data therefore points to high levels of program outcome attainment, enabled by effective training and development, consistent with the prior discussed research.

An internship strategy is more difficult to implement compared to a student pastor strategy as it requires churches to meet objective standards and be approved as a Partner Church,[117] involves a greater breadth and depth of structured learning experiences, and entails regular intern feedback and multisource evaluation from the pastoral leader and other church members. However, we believe that the extent of this additional difficulty is more than offset by the structured shape of the common student program each year, along with multiple custom training resources provided to Interns and their pastoral leaders during the program orientation.

Many apprentices in our wider Evangelical church culture are discouraged from engaging in degree-level study at a seminary or theological college until after the completion of their apprenticeship. In more recent years, some apprenticeship providers have encouraged formal theological training in addition to their training program. For example, Australia’s largest apprenticeship scheme offers prospective apprentices the opportunity to undertake training with at least six well-known training organisations.[118] This reflects a gradual shift and changing attitude in training – one that desires to integrate more coursework and formal training with their field experience. However, we have observed that much of the coursework and formal training that apprentices complete does not cohere with other elements in their training program (at least not explicitly), does not authorise them to serve as a pastoral leader, nor is it recognised by seminaries and theological colleges if apprentices continue training towards ordained pastoral ministry (normally another three to four years full-time study after their apprenticeship).[119]

The apprenticeship strategy is more difficult to implement than the previous strategies as the pastoral leader is responsible for overseeing, designing, implementing and evaluating the training program of a future leader with limited ministry experience or prior training, for more days of the week. The impact of this strategy on the future leader varies significantly, as much of the apprentice’s development depends on decisions made by the pastoral leader regarding the design and delivery of their program. We know several future leaders who have experienced high development outcomes through an apprenticeship strategy, as well as several who have experienced low development outcomes.

The two-year Traineeship has been in operation since 2023. The emerging leader development outcomes are promising, based on 360 surveys conducted at the start, middle and end of their program. Further details relating to the coherent design and consistency of outcomes we anticipate can be found in Appendix 2 and 3. Pastoral leader Coaches have reported that the Traineeship is less difficult to implement compared to their experiences with, and observations of, an apprenticeship strategy. The structured nature of the program design, the shared delivery model with the college, and the provision of training and resources for Coaches and Trainees contributes to this view.

A FRAMEWORK FOR EFFECTIVE TRAINING AND DEVELOPMENT

The prior discussed materials can be integrated together into a framework that summarises the cyclical nature of effective training and development (see Figure 4).

Future leaders and pastoral leaders should begin their training and development ‘journey’, not by ‘taking the next step’ or ‘enrolling in the best college’,[120] but by ‘looking before you leap’. This process begins with an analysis of stakeholder interests. Relevant training strategies and programs should be evaluated and selected, based on the following previously discussed factors:

- Alignment with stakeholder interests

- Coherence of program design

- Consistency of leader development outcomes

- Difficulty of implementation

Once a decision is made to select a particular training strategy and program, the future leader and pastoral leader can then engage in the associated training and development. As training and development progresses, leader development outcomes are evaluated. Program-level evaluation should produce reports for relevant stakeholders that inform important decisions and changes to be made in the next cycle of training and development.

CONCLUSION

This paper is our response to common questions from pastoral leaders and future leaders about effective training and development. Our views are shaped by our personal experiences of training and developing future leaders in Reformed and Presbyterian churches. They are informed by our observations of training and development in our wider Evangelical culture. They are supported by relevant research from multiple literatures. And they are embodied in training programs like the Christ College Traineeship and Internship. Although we believe our claims in this paper are true, and our recommendations are wise, their application in other contexts may be more limited.

As we have shared the views expressed in this paper with others, we have noticed two different kinds of reactions. For some, our framework will appear to be common sense. For others, it will be counter-cultural and challenge their assumptions about effective training and development.

Rather than follow the conventional advice most commonly given in our wider Evangelical culture of ‘take the next step’ or ‘enrol in the best college’, we recommend strongly that future leaders and pastoral leaders ‘look before you leap’. As argued earlier, analysing stakeholder interests, beginning with your own, is the first and most important category impacting on leader development. After this, the merits of various training strategies and programs can be evaluated according to their impact on leader development and difficulty of implementation. After an appropriate training strategy and program are selected, they can then engage in the training and development cycle summarised earlier in Figure 4.

For those interested in further detailed explanations and illustrative examples of these core concepts, we encourage you to read our appendices.