INTRODUCTION

Family life in Western culture is in the midst of an immense change sometimes identified as “the second demographic transition” (SDT). The term is used in a sociological theory which holds that a “post-modern” cultural preference for individuality and self-actualisation has engendered “sustained sub-replacement fertility, a multitude of living arrangements other than marriage, the disconnection between marriage and procreation, and no stationary population”.[1] Whether the explanation is correct need not detain us here. It is observable that, compared to historic patterns, in Western nations fewer people marry, while those who do marry are older than in previous generations and are more likely to divorce, fewer children are born and those that are more likely to be raised in a range of family structures.[2] Similar patterns have been observed in several non-Western cultures and developing nations. Families also face a range of pressures related to time, work, childcare, education, finance, housing and aged care. In this setting it is more important than ever to think theologically about families as a basis for ministry to and with families. This article particularly considers the relationship of church and family, setting both in the wider context of missio Dei. After a brief discussion of missio Dei and the definition of family, five theses will be presented about the place of family in God’s mission, culminating in the implications for church life and ministry.

MISSIO DEI

Missio Dei (the mission of God) is the most comprehensive description of the theme of the Bible and has been widely used as an integrating theme in contemporary theology.[3] We could say that the Bible is simply about God, more precisely it is about what God does and reveals through his acts and words — in one version “the glory of God in salvation through judgment”.[4] That is missio Dei. It is grounded in the two-fold mission of the Son and the Spirit, though this remains in the background in my discussion which will largely proceed at the level of a biblical theological study.[5] Our question is: to what extent and in what ways is ‘family’ part of God’s work and how does it relate to church?

FAMILY AND CHURCH

Families in the Bible are quite different to those in modern Western society. Most discussions of family in the Bible note varying social structures and the different terms used. [6] For the sake of brevity this review is omitted, noting what ‘family’ has in common in its various forms.[7] From Scripture we may conclude that human families exist because of the triadic relationship of husband, wife, and child formed by the creational institution of marriage. Varying structures develop from this triadic relationship, including households, tribes, clans, and dynasties.[8] While much of what follows applies to the nuclear family, it is important to note that ‘family’ is a variegated phenomenon. Similarly, this article considers the church in all its forms through redemptive history — the people redeemed and gathered by God to be his own community (Ge 17:7; Ex 6:7; 1 Cor 1:2; Heb 8:10; Rev 21:3).[9]

FAMILY IN MISSIO DEI

Even granting the obvious importance of family in the cultural context of the Bible, the theme of family is remarkably prominent and the plot of Scripture is largely about families. The following five theses highlight this theme in terms of how humans flourish in family life, how God utilises familial structures to bless and save humanity, and how the concept of family is transformed within the church.

1. HUMANS FLOURISH IN FAMILY RELATIONSHIPS

Family life is grounded in two creational structures — life-long monogamous heterosexual marriage and the relationship of father and mother to their children based in biological reproduction. That these relations are a divine ordinance for human society has been widely argued and disputed.[10] Here, the focus is on the importance of family in God’s creation purposes.

In God’s image we are relational (we are to love God and others), ethical (we are morally responsible), religious (we are to worship God) and viceregal (we rule for God). Each of these elements is bound into family life. The family provides and nurtures the most intimate human relationships. Our responsibilities to others begin with family relationships (Gen 4:9b; Exod 20:12,14; 1 Tim 5:4, 8). Religious life has roots in family life (Gen 4:3–4; 8:20; 12:7–8; 13:4, 18; 22:9; 26:25; 33:20; 35:1, 3, 7; Job 1:5). The cultural mandate (Gen 1:27-28; 2:23-24) is to be fulfilled through families as husbands and wives work together, raise children, develop human culture in God’s world and pass it to successive generations. When families function well, children come to maturity to take their own place in a family and in the wider society (Gen 24:66–67; 1 Sam 16:12–22; 17:1–18:5; Prov 3:35–4:27; 10:1,5; 17:6; 23:24). The opening chapters of Genesis show the family as the basis of human culture.[11] Underlying the importance of family in these ways is the fact that God relates in covenant to humanity through family solidarity.[12]

This is not to say that family life is the only setting for humans flourishing. Humans express their calling to be image bearers beyond family life. Those isolated from family can flourish. This is instanced by Joseph, who was separated from his family and left with deep pain (Gen 42-45), yet not only governed Egypt but became a man of impressive character.[13]

Of course, because family is foundational for human life, sin immediately impacts this domain. Marriage lost its harmony, childbirth became difficult, and the shared work of cultivating the fields became hard labour (Gen 3:7, 16-19). Cain hated and murdered his brother, and Lamech the bigamist threateningly boasted of his violence to his wives (Gen 4:5–8, 23–24). Family life is filled with violence and discord rather than providing a setting for flourishing (Gen 4:1-12; 4:23-24; 9:20-24; 37:18-35; Jdg 9:5, 39-50; 19:25-28; 1 Sam. 2:22–25; 2 Sam. 12:31–13:19; 1 Kings 14:1-18).[14]

The opening chapters of Genesis show the family as the basis of human culture. Of course, because family is foundational for human life, sin immediately impacts this domain. Marriage lost its harmony, childbirth became difficult, and the shared work of cultivating the fields became hard labour (Gen 3:7, 16-19). Cain hated and murdered his brother, and Lamech the bigamist threateningly boasted of his violence to his wives (Gen 4:5–8, 23–24). Family life is filled with violence and discord rather than providing a setting for flourishing (Gen 4:1-12; 4:23-24; 9:20-24; 37:18-35; Jdg 9:5, 39-50; 19:25-28; 1 Sam. 2:22–25; 2 Sam. 12:31–13:19; 1 Kings 14:1-18).

Despite the curse and the terrible effects of sin, God persevered in his work with and through families. He kept Noah and his family (Gen 6:18 cf 7:1, 7, 13; 8:16,18; Heb 11:7), repeated the cultural mandate to Noah (Gen 9:7) and made his covenant with Noah and his descendants (Gen 9:9–10). Underlying the importance of family in these ways, and especially displayed in Genesis, is the fact that God relates in covenant to humanity through family solidarity.

2. GOD RELATED TO ISRAEL IN FAMILY SOLIDARITY TO BLESS THE WORLD

The economies of creation and redemption are not far apart, God works through the structures which he ordains in creation and preserves in providence; and in redemption he restores and fulfils these. Family is key to God’s redemptive work.

The first promise of the gospel implies the place of family in redemption — one of Eve’s offspring is promised to crush the head of the serpent (Gen 3:15). The biblical account of redemption begins when God calls Abram from his father, promising to bless his family as a great nation through whom all the families of the earth will be blessed (Gen 12:1-5; 13:16; 15:4–5). God’s covenant relationship with Abram is also with his descendants “for the generations to come” (Gen 17:7). The sign of circumcision marked each of Abraham’s male descendants as a consecrated king-priest son of the Lord who could sire the next generation of the children of the covenant.[15] Abram (great father) was renamed Abraham because God would make him “the father of a multitude of nations” and kings (Gen 17:4–6). Redemption runs through this elect family.

Abraham was promised that all the families (mispaha) of the earth would be blessed through him. It is sometimes suggested that this description belittles the claims of the other nations — they are only families.[16] However, the parallel passages (Gen 18:18; 22:18; 26:4) refer to blessing nations (goyim). Given the importance of family in the Genesis narrative, it is unlikely that the term mispaha is disparaging. On the other hand, the theme of the blessing of the nations is so extensive in Scripture; and the nations continue to appear in the eschatological passages in the book of Revelation (Rev 21:24, 26; 22:2). There is no reason to privilege family over nation in God’s purposes nor vice versa, each has its place in God’s economy.

God’s promise stood in tension with Abraham’s actual childlessness. In the key dramatic moment God called him to sacrifice his long awaited son. The rest of Genesis traces the growth of Abraham’s family till Jacob’s household numbered seventy (Gen 46:27). By the start of Exodus, Israel was fruitful “and multiplied greatly and became exceedingly numerous” (Exod 1:7). The promise of a blessed family had been partially fulfilled. It was this promise to Abraham that directed the history of Israel (Gen 26:24; 28:4; Exod 2:24; 3:6; 6:8; Lev 26:42; Deut 1:8; 9:5; Josh 24:2; 2 Kgs 13:23; Isa 29:22; 41:8; 51:2; Jer 33:26; Mic 7:20). Moses was told that the Lord was “the God of your father, the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob” (Exod 3:6). The reason for Israel’s redemption and possession of the land was God’s promise to their fathers (Deut 6:3,10; 9:5; 10:22).

The national covenant with Israel instituted at Mount Sinai was grounded in family solidarity. The covenant with the Sinai generation included later generations (Deut 5:3). In the covenant renewal ceremony of Deuteronomy 29, the Lord stated that the covenant was with “whoever is not here with us today” (Deut 29:15), that is with future generations.[17] Yet the fact of a covenant renewal for the present generation implies that future generations will also require covenant renewal (Josh 24; 2 Kgs 11:17; 23:1–3; 2 Chr 23:3; Ezra 10:3; Neh 9:38). Each generation inherited the covenant from their parents but had to embrace the covenant.[18]

The importance of the family in Israel was underlined when the Lord proclaimed his identity to Moses (Exod 34:6-7 c.f. Num 14:18; 2 Chr 30:9; Neh 9:17; Pss 86:5, 15; 103:8; 111:4; 112:4; 116:5; 145:8; Joel 2:13; Jonah 4:2) and his promise to forgive thousands is directed to the generations of Israel, a text which is repeated and alluded to multiple times in the Old Testament.[19] Cassuto comments that the Lord gave an “assurance that the beneficent results of their love will endure in the life of the nation and be bestowed upon the children and the children’s children and upon their descendants up to thousands of generations … to the end of all generations”.[20] The genealogies of Israel (1 Chr 1–9; Gen 19:30–38; 22:20–24; 25:12–26; 36; 46:8–27; Exod 6:14–25; Num 3; 26; Ruth 4:18–22; 2 Sam 3:2–5; 5:13–16; Ezra 7:1–5; Esth 2:5–6; Matt 1:1–17; Luke 3:23–38) show that God worked through the generations of Israel and was their God because he was the God of their fathers.

The covenant with David was about his dynasty, the Lord would build a house for David and take David’s son as his son. David’s kingdom, Israel’s future, and God’s work to bless the nations were all secured on that basis (2 Samuel 7:11–16). The restoration of the house of David is then an important theme in the prophets (Isa 9:7; 16:5; 22:22; 55:3; Jer 17:25; 23:5; 30:9; 33:15, 17, 22; Ezek 34:23–24; 37:24–25; Hos 3:5; Zech 12:8, 10).

The family is not the only level at which God is at work in Israel. From the family of Abraham, he built a nation and he dealt with the whole nation. He demanded a response not just from each generation but from every individual (Ezek 18:1-32). God works through families, but not through families alone.

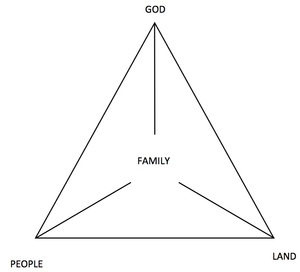

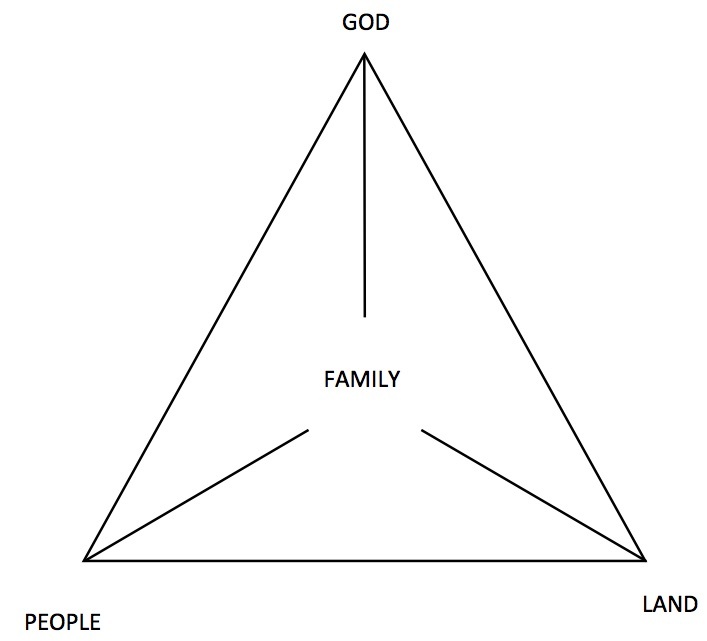

Israel’s life as a holy nation depended on families. Chris Wright describes the life of Israel as a triangle of relationships: “the Lord, as the God of Israel; Israel themselves as an elect people in unique relation to the Lord; [and] the land of Israel … the Lord had promised and given to them” — the theological, social and economic angles.[21] He observes that “the household-land unit was central to the triangle of relationships between God, Israel and the land”. The “house of the father” (bet ab) was the basic unit for social relationships, for the possession of the land and economic life and was pivotal in the “experience of the covenant relationship”. Israel lived in the land as an inheritance distributed to them in families (Lev 25:25-28; Num 26:52–56; 27:8–11; 1 Kgs 21:3). Faithfulness to the Lord required social and economic justice, including properly ordered family life and the protection of the rights of families. The theological, social and economic “angles” of Israel’s life “had the family as their focal point”.[22]

Israel’s faith was to be shared and holy living taught in the family. Fathers were to set an example of faithfulness to the Lord and to teach their children his word and his ways (Deut 4:9; 6:6–7; 11:19; 32:46; Ps. 78:4-6). “The Pentateuch, the Old Testament historical books, and the book of Psalms are pervaded by the consciousness that parents (and especially fathers) must pass on their religious heritage to their children”.[23] Wisdom literature is concerned with raising children well and instructs children as well as parents (Prov 1:8; 6:20: 13:24; 23:13-14).[24] Key religious ceremonies were conducted in families: circumcision (Lev 12:3), the Passover (Ex 12) and the consecration of the first born (Exod 13:1-16). The national assemblies for Passover and the other feasts (Lev 23:1-21) had a family dimension (Duet 16:1-15 cf v16).

Israel’s law provided extensive protection for the family. Parents were to be honoured and obeyed (Exod 21:15, 17; Duet 21:18-21; 27:15) and were responsible to not show favouritism (Duet 21:15-17). Sexual laws protected the integrity of marriage and the family. Every family was given a share in the land (Josh 13ff) as their inalienable possession (Lev 25:23). If this were to be sold or forfeited, it was redeemed and restored in the year of Jubilee (Lev 25:24-55). The land was preserved for the nation through family inheritance. Israel could be the holy nation and a light to the nations only as families remained faithful to the Lord so each generation would continue to live for him.[25] The mission of God ran through the families of Israel.

The Old Testament bears eloquent testimony to the importance of the family for the life and faith of Israel in its portraits of family failure. Chris Wright observes that the families of the patriarchs “could fill a comprehensive casebook on dysfunctional families”.[26] Family after the patriarchs is much the same (e.g. Num 12; 16; Josh 7). Intermarriage was prohibited because it would take Israel away from the Lord to worship other gods (Exod 34:15-16; Josh 23:12, 13; 1 Kgs 11:2; Deut 7:3-4), though that came to pass (Jdg 3:6; 1 Kgs 11:1-8; Mal 2:11). The royal households were corrupted by mixed marriages and were examples of almost all that could go wrong in family life. The prophets present the corruption of family life in Israel and Judah as part of their description of the sins of God’s people. Social injustice robbed families of their inheritance (Mic 2:1-2, 8-9; Isa 5:8-10); families were divided within (Mic 7:6) and familial responsibilities ignored (Isa 3:5).

For all the importance of families in the life of Israel, there was more to the nation than families. The wider roles of judge, king, prophet, priest and wise man were equally crucial. Worship occurred in families but was centralised at the temple (Deut 14:23; 15:20; 1Kgs 5:5; 9:3; 2Chr 2:4; Pss 26:8; 78:68). Families travelled to the temple to offer sacrifices and participate in festivals. The interconnection between family life and wider institutions of Israel is illustrated vividly in the failure the family of Eli (1 Sam. 2:27–36; 3:11-14) and the corruption of royal households. In both cases domestic failures had severe consequences for national life.

3. GOD’S WORK WAS ACCOMPLISHED THROUGH THE BIRTH OF THE CHRIST TO A FAMILY IN ISRAEL AS THE START OF THE NEW HUMANITY

The mission of God to bless the world through Israel seemed to come to an end with the exile. Yet from this came the great prophetic promises. To what extent does the prophetic hope rest in the family? That is related to the question of whether Old Testament eschatology is messianic. Does its hope focus on a saviour from Israel and the house of David?

Major elements in the Old Testament hope, for instance descriptions of “the Day of the Lord”, look to the Lord’s direct intervention (Isa 24:21–22; 27:1–13; Jer 30:7–8; Mic 4:1-8; Zeph 3:8–20; Zech 14:20–21; Mal 4:1–3). Yet even the Day of the Lord has messianic dimensions (Isa 11:10; Jer 30:9; Hos 3:5). More generally, the motif of a saviour who will come from within Israel is woven through the prophetic literature (Isa 49:5–7; 52:13–53:12; 61:1–3; Zech 4:13–14). He is usually described as a king (Zech 6:12–13; 9:9–10), often explicitly from David’s line (Isa 11:1–9; Jer 23:5–6; Ezek 34:23–24; 37:24–25; Mic 5:1–4; Zech 9:9–10; 12:10).

The theme of the redemption of Israel and the accomplishment of God’s mission through the birth of a child to the family of David is most explicit in Isaiah 9. The previous chapters are heavily ironic, using the birth of children to convey a message of judgement on the house of David, the family which is central to the identity and destiny of Israel.[27] The prophet’s own children represent both the promise of a remnant of the people (Shear-Jashub, Isa 7:3) and the threat of judgement on the house of David (Maher-Shalal-Hash-Baz, Isa 8:1-4). King Ahaz was warned of the fate of his house through the sign of the birth of a son, “Immanuel”, to a young woman, or virgin (Isa 7:14–17). Before the child grew up Syria and Ephraim would be defeated. This was portent, not reassurance, for Ahaz feared Judah’s enemies more than he feared the Lord and was tempted to seek an alliance with Assyria (2 Kgs 16:7). God would not only deal with Syria and Ephraim, but because the Lord was with Judah, Assyria would come on Jerusalem (Isa 7:17-25; 8:5-10).

Chapter 9 then takes up the hope represented by Shear-Jashub. A son will be born who will take the throne of David and enjoy the promises of 2 Samuel 7 (Isa 9:6-7). The prophecy of the shoot from the stump of Jesse (Isa 11:1) continues the theme of a new Davidic king. Within the broader messianism of the Old Testament, Isaiah draws the focus onto the promise of the birth of a son to the house of David as the key to Israel’s hopes. Yet this child would only come after the judgement of the house of Israel, Jesse was to be reduced to a stump before there would be a shoot.

The prophetic picture of the redemption of Israel includes the restoration of family life. The new creation at the end of Isaiah is “a place in which families are safe from infant mortality over early death and the fruit of family labour will not be frustratingly swept away” (Isa 65:17-25).[28] There is also a strong sense of family solidarity in one of the climactic phrases in the eschatological description: “They shall not labour in vain or bear children for calamity, for they shall be the offspring of the blessed of the LORD, and their descendants with them” (Isa 65:23). This is a promise of the end of Adamic curses on work and childbirth and of generations living under God’s inherited blessing.

The gospel of the nativity is that the promised Saviour has been born in Israel, to the house of David and he meets all the hopes of Israel and completes the work of God for the world. His birth echoed the creation and fall narrative. The presence of the Spirit in the annunciation narratives, and especially the statement that he will “overshadow” (episkiazo) Mary (Luke 1:35), evokes the Spirit ‘hovering’ over the waters of Creation. Because of the overshadowing Spirit, he would be the “Son of God” (Luke 1:35). Luke’s genealogy traces Jesus’ lineage back to “Adam, the son of God” (Luke 3:38). Jesus is the son of Adam, the new Adam, and the beginning of a new creation, or re-creation.

Jesus is also the fulfilment of the promise to Abraham. Matthew’s genealogy, immediately preceding the annunciation, names Jesus as “the son of Abraham” (Matt 1:1–2 c.f. Luke 3:34). Mary and Zechariah recognized Jesus as the child who fulfills the promises to Abraham (Luke 1:55, 73). Paul makes the connection explicit stating that the promise was made “to Abraham and to his seed… meaning one person, who is Christ.” (Gal 3:16).

The annunciation of Jesus’ birth established that he is a descendant of David (Matt 1:20; Luke 1:27, 32-33). Isaiah’s promise of a Davidic messiah is the key to Matthew’s presentation of annunciation, as Matthew explains that "this took place to fulfill what the Lord had said through the prophet: “The virgin will conceive and give birth to a son, and they will call him Immanuel” (Matt 1:22–23). The same theme is also clear in Luke’s nativity account for the Lord “has raised up a horn of salvation for us in the house of his servant David” (Luke 1:69 c.f. 1:27, 32; 2:4, 11; 3:31).

Jesus from the line of Adam, Abraham and Moses, was conceived by the Holy Spirit (Matt 1:20; Luke 1:35) and born to a virgin. In him God brought about a new Israel and a new humanity.[29] He is the new Adam, head of a new creation; the child of Eve who crushes the head of the serpent. He is the seed of Abraham who will bless the nations. The stump of Jesse could not shoot of itself; God brought the true shoot. Jesus was born to faithful family (Luke 1:6, 38; Matt 2:19), was circumcised on the eighth day and presented at the temple (Luke 2:22-24). Consistent with the character of his family, he matured in wisdom and grace with a developing sense of his own vocation (Luke 2:40, 49, 52). The family tree of Abraham bears its sweetest fruit in Jesus.

In light of Jesus’ coming, John the Baptist confronted Israel with the prospect of God’s judgement (Lk 3:7) warning that they cannot presume on their ancestry as “children of Abraham”. In one sense this is simply to repeat the Old Testament theme that every generation must renew the covenant. John’s message introduces an extra note: just as Abraham was the rock from which Israel were cut (Isa 51:1-2), God can raise up children for Abraham out of the stones (Lk 3:8).[30] The tree of Israel faces the axe and fire, the children of Israel will continue through the one born in Israel who will call the nations (Lk 2:31-32; 24:47), the beginning of a new humanity.

4. GOD’S WORK IN CHRIST RECONFIGURES FAMILY RELATIONSHIPS: ESTABLISHING A COMMUNITY IN CHRIST WHICH TRANSCENDS AND INCLUDES FAMILY RELATIONSHIPS

The birth Jesus could mark the end of the theological significance of family. Coljin suggests just this: “the role of the family in salvation history is fulfilled and brought to completion in Jesus”.[31] This overstates the case. The purpose of family and the promises to Abraham’s seed are fulfilled in Christ, yet family remains important in God’s mission. In fulfillment, family relationships are reconfigured and the family has a somewhat different place in God’s mission.

Jesus placed loyalty to God over family expectations (Matt 12:50; Mark 3:35; Luke 2:41–51; John 2:4) and expected the same of his followers (Luke 9:59–62), demanding a more decisive separation from parents then Elijah required from Elisha (1 Kings 19:20).[32] He warned that he and his kingdom divide families (Matt 10:35; Luke 12:53). Jesus said his disciples must “hate” their family and “even their own life” (Luke 14:26).[33]

Jesus also established around himself a new family, or in Hellerman’s terms, a “surrogate kin group”.[34] He identified his disciples as his family members (Matt 12:48–50; 25:40; 28:10), described his disciples as brothers to one another (Matt 18:35; Luke 6:41–42; 17:3; 22:32) and promised that those who left house, family and lands for his sake would receive “a hundredfold now in this time” and eternal life (Mark 10:29–30). In the new company of God’s people disciples gain “brothers, sisters, mothers, children”. This is not simply a continuation of the practice of calling fellow Israelites brothers (Gen 29:4; Lev 25:25, 35–36, 39, 46–48; Deut 15:7, 9, 11–12; 17:15; Ps 22:22; Acts 2:29; 3:17; 7:2; 13:15, 26, 38; 22:1; 23:1; 28:17), but part of a counter-cultural pattern. The call to break family ties brought shame and economic risk, since in a “collectivist” Mediterranean culture “a person … bereft of a primary group exists, socially speaking, on the brink of death”.[35] Jesus created around himself a community distinct from the natural family, which had a priority over the family.

Jesus’ new community does not remove the family from missio Dei. He affirmed the sexual and family ethics of the Old Testament, including faithfulness in marriage (Matt 19:1-8) and responsibility to parents (Matt 15:3–7; Mark 7:9–13). These creational structures have a place in his kingdom. The scene during Jesus’ crucifixion in which he gives his mother to the beloved disciple shows the realignment of family life from his ministry (John 19:25–27). Mary’s presence and Jesus’ concern for her demonstrates the ongoing significance of family ties. Yet there is a new relationship, beyond family ties, between Jesus’ followers. Mary and John are mother and son. When family loyalty is set against following Christ, then Christ must come first; yet the two sets of relationships can be complementary, as they were in this case. Jesus fulfills his filial responsibility by entrusting his mother to his disciple and friend.

This shift in relationships comes to full expression in the epistles and the evidence from these can only be sampled. The creational structures of family find their fulfillment in the Pauline theme of the adoption of believers (Gal 4:5; Rom 8:15, 23; Eph 1:5) and the more general New Testament teaching that believers are God’s children (Matt. 5:9; Jn 1:12–13; Rom. 8:14, 16, 21; Eph. 5:1; 1 Jn 3:1–2, 10).[36] God is Father (Rom 8:15; Gal 4:9) and believers are his children through Christ who is the firstborn Son (Rom 8:29). The creational patterns are typological, the archetype is the communion of God and his people in Christ.

This has implications for the relationship of believers who are brothers and sisters (Phil 4:1). Banks identifies this as the root metaphor for Paul’s understanding of his relationship to the church.[37] Hellerman points out the image established the kind of relationships which believers should have with each other. They are to relate as siblings with reciprocity (1 Cor 6:1-11,2 Cor 8-9; Gal 4:15), truthfulness and common behaviour (1 Cor 4:14-17; 2 Cor 8-9; 1 Thess 1:4-7; 2:14). This new bond takes a priority in loyalties (1 Cor 7:12-16).[38] Paul used family imagery for his own relationship to the church — he was like a mother (1Thess 2:7), father (1 Cor 4:14; 2 Cor 6:13; 1 Thess 2:11 c.f. 3 John 4) and a household steward (1Cor 4:1; 9:17 cf 1 Pet 4:10).

The place which the New Testament allows for singleness indicates the shift in the significance of family with its fulfillment in Christ. In the Old Testament an unmarried adult was rare and had probably suffered a terrible misfortune. Jeremiah seems to be unique in being called by God to be single, at least for a time (Jer 16:1-4).[39] In contrast, both Jesus and Paul were single (1 Cor 7:8; 9:5) — if perhaps Paul was a widower.[40] Both teach about the possibility of being single for the sake of the mission of God (Matt 19:12). Paul extols the freedom of the unmarried to be “anxious about the things of the Lord, how to please the Lord” (1 Cor 7:32). Because marriage and family are fulfilled in Christ gives a new family group, some believers live outside marriage and family.

The eschatological material of the New Testament raises the question of whether, ultimately, natural family ties become insignificant in the kingdom of God. Scobie’s suggestion that “the family unit fades from view and is replaced by a more corporate vision of the whole family of God” goes beyond the evidence. [41] Family life is not ended but consummated and transformed. Jesus teaches that in the kingdom there will be neither marrying nor giving in marriage. Yet the final day is a wedding feast with the people of God represented as the new Jerusalem which is “prepared as a bride beautifully dressed for her husband.” (Rev 21:2). The eschaton is also the fulfilment of Isaiah’s eschatology with the city filled with children.

To what extent does eschatological consummation, glorification and transformation mean that family structure is transcended? Scripture draws a veil around the details of the new creation, telling us that “what we will be has not yet been made known”, beyond that we will be glorified with Christ (1 John 3:2). What we can say is the family is not abolished but consummated and transformed, though the precise nature of that transformation is yet to be revealed.

5. GOD’S WORK IN CHRIST RESTORES FAMILY AND RECRUITS IT FOR HIS MISSION

The natural family is redeemed in Christ and transformed to serve God and is recruited for his mission. Paul warns that “if anyone does not provide for his relatives, and especially for members of his household, he has denied the faith and is worse than an unbeliever” (1 Tim 5:7–8). The household codes offer a study in how Christ redeems life and makes the household a key arena for discipleship. They assume the ongoing importance of family structures. Paul quotes Genesis 2:24 in Ephesians 5:31 and applies the fifth commandment to children (Eph 6:2–3). Peter instructs wives to follow the example of obedient Sarah (1 Pet 3:6). They address the effects of sin, husbands are taught to love their wives (Eph 5:28-29); fathers to not provoke their children (Eph 6:2); slaves to please their masters consistently; masters not to threaten nor to show favouritism (Eph 6:9) nor be harsh (1 Pet 2:18). Apostolic paraenesis assumes the social structures and mores of the culture (Tit 2:5,8,10, yet household relations are claimed as an avenue for service of Christ and others for Christ. The apostles call for radically countercultural stances, especially of love and service.

Households were recruited into missio Dei as they turned to Christ (Acts 11:14; 16:31–34; 18:8; 1 Cor 1:16; 16:15). Paul often based his mission work in a welcoming household (e.g. Acts 16:11-15; 18:7; 20:20; 21:8, 16). Households hosted churches (Rom 16:5; 1 Cor 16:19; Col 4:15; Phlm 1:2). As in Israel, children were to be raised in the “discipline and instruction of the Lord” (Eph 6:4 c.f. 2 Tim 1:5; 3:15). A Christian married to an unbeliever could influence him or her toward faith in Christ (1 Pet 3:1-6, 1 Cor 7:12-16).

IMPLICATIONS FOR CHURCH LIFE AND MINISTRY

The biblical-theological survey highlights the foundational significance of family for human life and Christian discipleship. It clarifies ways in which family connects with church, and ways in which the two are distinct. It also reminds us of ways in which family life goes wrong. All of this has implications for church life and ministry in the context of the SDT.

FAMILY LIFE AND THE COMMON GOOD

Family based in life-long monogamous heterosexual marriage and biological reproduction is a foundational element of human life. For the sake of the common good, Christians should be concerned about families in our societies and ready to invest in their support and protection. This calls us to care about marriage, divorce, and adoption, as well as the impact of socio-economic factors on families.[42]

Family is more complex than the nuclear family.[43] It includes families formed by adoption,[44] as well as single parent and blended families. Christian thought about family needs to include all these and must consider the range of patterns of family life in modern culture and how they should be understood and supported, though that is beyond the scope of the current article.

FAMILY AS IDOL

Because family is such a good, it is prone to become an idol. As the basis for identity and a source of protection, nurture, comfort, intimacy, purpose, stability and joy: it makes a powerful god.[45] Jesus calls people away from family to follow him and says disciples must “hate” their family (Luke 14:26). This text is relevant when families demand a loyalty which rivals Christ, but it also warns us not to offer such commitment. In middle-class Australian culture Christian ministry will call people away from devotion to family to a first devotion to Christ.

CORRUPTION OF FAMILY

There is a risk we will overlook the reality of the corruption of family life and the devastation which can flow from that. The Latin phrase corruptio optimi pessima (“The corruption of what is best is the worst”) captures this reality.

To give one example, a 2011 Australian study found that for women aged 25-44 years, Intimate Partner Violence was the single most significant contributor to “burden of disease”.[46] That is, it has the single largest negative impact on health of young women in Australia.[47] We could examine similar impacts of conflicted marriages, divorce, abusive parents and many other ways in which family life is corrupted.[48] Health is not the only measure of the impact of family life, but it provides an easily measurable one.

Pastoral care must not assume that families are benign and make a positive contribution to human flourishing. While we rightly wish to help people to remain well connected with their families, we should recognise that for some that is dangerous and even destructive.

FAMILY IS NOT CHURCH, AND THE CHURCH IS NOT THE FAMILY

The church has a place which the family must not supplant. Since Vatican II, Catholic theology has renovated the concept of the domestic church (ecclesia domestica).[49] This idea has its roots in the New Testament material surveyed above and was used to emphasise the importance of family life in a tradition which had assumed that a religious vocation required separation from family life. Yet, the description of the family as a “little church” can be misleading, especially in evangelical circles with a relatively low view of the institutional church.[50] The family cannot provide all we need for Christian living. We need the teaching, care, fellowship, worship, and discipline of the church — a wider community. The sacraments are not administered in the family, but when the church gathers with the leadership of the ordained ministers of the church. Paul rebukes the Corinthians that they can hold their “private suppers” in their homes, but should share “the Lord’s Supper” in the fellowship of the church (1 Cor. 11:17–22).[51]

On the other hand, the church cannot replace the family. Family is a unique institution in human life and cannot be successfully exchanged for any other institution — not even the church. In the eschaton the various institutions (family, church, city, state) seem to be drawn together as each of these typological institutions are fulfilled in the fellowship of the Triune God with his people. In this age, each needs to be recognised and given its place in human life and in Christian living.[52]

CHURCH IS NOT A FAMILY OF FAMILIES

The church is not simply an aggregate of families. This has important implications for men and women working together in church. It also clarifies that churches should not communicate that unmarried members need to have a place in a family in order to have a place in church. Along similar lines Bronwyn Lea argues that men and women should relate in church as brothers and sisters, with the freedom and respect of siblings. Our relationships are not simply determined by our family roles.[53]

DISCIPLESHIP IN FAMILIES

Missio Dei restores creational order and includes it in the economy of salvation. While Christ calls disciples from total loyalty to family, he also sends them to serve in families.[54] Christian discipleship is not cut free of family life, and for most Christians the family is a key area in which they serve the Lord. For many, though not all, faith is nurtured in a family.

The ongoing place of family in missio Dei is an important part of the Reformed argument for covenant baptism. Children in Christian families belong to the Lord (Eph. 6:1; Col. 3:20; 2 Tim. 3:15), are part of the church of Christ, receive the promises of the covenant (Acts 2:39), and so receive the sign of the covenant.[55] This paper sets out a reading of Scripture which supports such a covenant theology view, rather than an approach such as New Covenant Theology.[56] The intent is to show a wider basis for, and the implications of, such a view of family and missio Dei, rather than arguing primarily for a view of baptism.

Churches and Christian ministries should respect the place of family life. This will include thoughtful scheduling of meetings and encouraging members to invest time and energy in immediate and extended family relationships. Any movement which denies or denigrates family life, including ongoing connection with unbelieving family members, should be viewed with suspicion. ‘Cults’ often demand the revocation of family ties. While authentic Christian ministry will call on people to put Christ above their family, it will also help them to discern how to serve Christ in their family. Preaching, Christian education and pastoral care should address people in their family relationships, offer a biblical vision of serving their families and support them through the challenges of family life. Not all believers are part of a ‘Christian family’ — ministries must include single people, those married to non-Christians, children with unbelieving parents and parents with unbelieving children.

The Bible assumes that parents who are faithful to the Lord will raise their children in the faith; and that family life is effective and important for passing on the faith. Models of ministry which focus on church or school, without a very clear and considered place for family fall short of a biblical vision. Ministry to children and youth in the church should start with ministry to their parents, encouraging and equipping them to raise their children. The traditional Reformed emphasis on the importance of family worship needs to be encouraged, even as we explore new forms and modes for 21st century families.[57]

FAMILIES LOOK OUTWARD

God’s concern is not exclusively with the family. It extends to wider society, and God’s kingdom is anticipated now in the church. A Christian family will be turned outward, seeking to serve a church and neighbours. The importance of family life does not justify insular family life. In the early 1980s Faith Popcorn identified a growing trend in Western culture of “cocooning” in which people and families spend more time at home sheltering from the stresses and threats of the outside world. The COVID pandemic has only increased this trend, as we have been forced to work, study, shop, relax and worship from home.[58] This pattern can turn Christian families in on themselves, withdrawing from church and any unnecessary involvement in culture. The challenge for churches and families is to cultivate family life in a way which is engaged in mission.

FAMILIES AND CHURCH LEADERSHIP

Family life is included in the list of qualifications for church leaders in the pastoral epistles (1 Tim 3:2-5, 12; Tit 1:6) and Smith argues that the structure of the lists indicates that family life is “the most important criterion”.[59] The meaning of and application of the qualifications has been debated.[60] The relevant point for this discussion is that the connection between family and church is such that that an ability to manage one’s own family is a prerequisite to care for God’s church. More generally, unlike most employment in contemporary culture, leading church in a paid or unpaid position, necessarily involves a person’s family. Selection, training and care for church leaders should take this into account.

CONCLUSION

This survey demonstrates how family is a major biblical theme and should be a significant concern for Christian ethics and ministry. As 21st century Western culture continues this “second demographic transition”, it is imperative to understand family from its place in the mission of God, especially when considering how Jesus calls disciples beyond family life, but also to return to family life to serve him. Family should be a serious focus in social ethics and ministry, whilst simultaneously recognising that the gospel relativises the claims of family and calls us beyond it.

F. Goldscheider, E. Bernhardt, T. Lappegård. “The Gender Revolution: A Framework for Understanding Changing Family and Demographic Behavior” Population and Development Review 41. 2 (2015): 208, quoting research from R. Lesthaeghe & J. Surkyn “When history moves on: The foundations and diffusion of a second demographic transition” International Family Change: Ideational Perspectives (New York: Lawrence Erlbaum, 2008), 81–118; R. Lesthaeghe “The Unfolding Story of the Second Demographic Transition” Population and Development Review, 36(2010): 211–51; R. Lesthaeghe The second demographic transition: A concise overview of its development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2014; D.J. van de Kaa. “Postmodern Fertility Preferences: From Changing Value Orientation to New Behavior” Population and Development Review. 27 (2001):290–331.

L. Qu, Families then and now, 1980–2020. (Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies, 2020) https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2020-07/apo-nid306881.pdf.

For an overview of the development of the theme in contemporary theology see M. T. B. Laing, “Missio Dei: Some Implications for the Church,” Missiology 37/1 (2009): 89-99.

J. M. Hamilton, God’s Glory in Salvation Through Judgment: A Biblical Theology (Wheaton: Crossway, 2010), 47-59.

D. Sarisky, “The Meaning of the Missio Dei: Reflections on Lesslie Newbigin’s Proposal That Mission Is of the Essence of the Church”, Missiology 42/3 (2014): 259-63.

See D. Block, “Marriage and Family in Ancient Israel” 134-37, and S. Treggiari, “Marriage and Family in Roman Society”, 145-46 in Marriage and Family in the Biblical World, ed. K. M. Campbell; (Downers Grove: IVP, 2003); C. Meyers, “The Family in Ancient Israel”, 11-21; J. Blenkinsopp, “The family in first temple Israel”, 49-53; J.J. Collins, “Marriage, divorce and Family in second temple Judaism”, 105; and L.G. Perdue, “The Israelite and Early Jewish Family”, 174-78 in Families in Ancient Israel: The Family, Religion, and Culture, eds. L. G. Perdue et al., (Louisville,: Westminster John Knox, 1997); J.S. Jeffers, The Greco-Roman World of the New Testament Era: Exploring the Background of Early Christianity (Downers Grove: IVP, 1999), 238-41; M.S. Lawson “The Old Testament Teaching on the Family”, and R. Melick Jr. “New Testament Teachings on the Family”, M&M Anthony eds, 2011.

J. F. Drinkard, “An Understanding of Family in the Old Testament: Maybe not as Different from Us as We Usually Think” Review & Expositor 98/ 4 (September 2001): 487.

H. Bavinck, The Christian Family, (Grand Rapids: Christian’s Library Press, 2012),7; E. J. Echeverria, “Bavinck on the Family and Integral Human Development” The Journal of Markets & Morality 16/1 (2013):220-21.

See E.P. Clowney, The Church (Downers Grove: IVP, 1995), 27-60; C. van der Kooi and G. van den Brink, Christian Dogmatics: An Introduction (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2017), 580-83; J. McClean “Living in God’s Mission: Theses for a Systematic Ecclesiology” Beyond Four Walls: Explorations in Being the Church. M.D. O’Neil, Peter Elliott, eds (Eugene: Wipf and Stock, 2020), 113-32.

See A.J. Köstenberger and D.W. Jones, God, Marriage, and Family: Rebuilding the Biblical Foundation, (Wheaton: Crossway, 2010, 2nd ed, Kindle), loc. 341-430; J. Murray, Principles of Conduct. (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1957), 45-81; W.L. Kynes, “The Marriage Debate: A Public Theology of Marriage.” Trinity Journal 28.2 (Fall 2007): 190-91; B.N. Peterson, “Postmodernism’s Deconstruction of the Creation Mandates.” JETS 62.1 (March 2019): 128–36; W. Kaiser, Toward Old Testament Ethics, (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1991), 153-54; H. Thielicke, Theological Ethics, Vol. 3: Sex. (Grand Rapids,: Eerdmans, 1969), 101-24; Bavinck 2012, 1–8 cf E.J. Echeverria, 219–37; O. O’Donovan, “‘One man and one woman’: The Christian doctrine of marriage”, 268-89 in Marriage, Family and Relationships: Biblical, Doctrinal and Contemporary Perspectives, (London: IVP, 2017).

“The primary unit of society according to the Old Testament is the family”, Drinkard, 487. It is possible that human life could be arranged without marriage and family, but it is not clear that there is any human culture which has done so. Hua Cai, A Society without Fathers or Husbands: The Na of China, (trans. A. Hustvedt; New York: Zone Books, 2001) claims that the Na or Moso in Yunnan in China have no marriage and do not recognise the place of fathers. His conclusions are contested, see for example N. Tapp, review in The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 8/3 (2002): 601-02.

I assume, without arguing for it here, the standard Reformed view that Adam was the head of humanity on the basis of family solidarity.

S. F. Hunter and M. G. Kyle, “Joseph,” James Orr et al. ed., The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia (Chicago: Howard-Severance, 1915), 1740, note “hi nobility of character, his purity of heart and life, his magnanimity as a ruler and brother”.

A. Errington, “On male violence: a theological reflection on Genesis 4:19–24”, St Marks Review, No. 243, (March 2018): 114-22; R. Nauta, “Cain and Abel: Violence, Shame and Jealousy.” Pastoral Psychology 58, no. 1 (March 2009): 65–71.

Gentry and Wellum, 272-74.

Gentry and Wellum, 243-44; W.J. Dumbrell, Faith of Israel: Its Expression in the Books of the Old Testament (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1988), 24.

P. C. Craigie, The Book of Deuteronomy (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1976), 357; D. L. Christensen, Deuteronomy 21:10-34:12 (Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 2002), 718.

J. A. Thompson, Deuteronomy: An Introduction and Commentary (Downers Grove: IVP, 1974), 281-82.

A. Petterson, “The Flying Scroll That Will Not Acquit the Guilty: Exodus 34.7 in Zechariah 5.3”, JSOT 38/3 (2014): 354-55.

U. Cassuto, A Commentary on the Book of Exodus (Jerusalem: Magnes, 1967), 243.

C. J. H. Wright, Old Testament ethics for the people of God (Leicester: IVP, 2004), 19; see the whole discussion pp 17-99.

Wright, 339-40.

Köstenberger, loc. 1799.

C. H. H. Scobie, The Ways of Our God: An Approach to Biblical Theology (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2003), 809; Köstenberger, loc. 1818.

W. Janzen, Old Testament Ethics. A Paradigmatic Approach (Louisville: Westminster/John Knox, 1994) suggests family is the central paradigm in Old Testament ethics related to four others (priestly, sapiential, royal and prophetic) which feed into and are nourished by it.

Wright, 343.

G. Goswell, “Royal Names: Naming and Wordplay in Isaiah 7,” WTJ 75/1 (2013):109 summarises “There is a future for a purified remnant but no guaranteed future for the Davidic line”.

Wright, 346.

H. Bavinck, Reformed Dogmatics, J. Bolt, ed., J. Vriend, trans., 4 vols. (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2003), 3:93-95.v

The parallel is accentuated since there is a likely pun between “stones” and “children”, abanim/ banim (Hebrew) or bĕnayyāʾ / ʾabnayyāʾ (Aramic); see J.R. Edwards, The Gospel according to Luke, (Grand Rapids/ Nottingham: Eerdmans /Apollos, 2015), 111; D.W. Pao and E.J. Schnabel, “Luke,” in Commentary on the New Testament Use of the Old Testament D.A. Carson et al eds (Grand Rapids/ Nottingham : Baker / Apollos, 2007), 278.

B. B. Colijn “Family in the Bible: A Brief Survey” Ashland Theological Journal 36 (2004), 76 though she also notes that “in the New Testament, the family again becomes a center of religious life”.

Pao and Schnabel, “Luke”, 316.

Edwards, Luke, 426 comments that “‘hate’ should not be understood in terms of emotion or malice, but rather in its Hebraic sense, signifying the thing rejected in a choice between two important claims”.

J. H. Hellerman, The Ancient Church as Family (Minneapolis: Fortress Pres, 2001), 64-73.

J.V. Kozar, “Forsaking your mother-in-law to go fishing: the call of the first disciples in Mark and the abandonment of family ties as exemplar of Markan discipleship (Mark 1:9-39)”. Proceedings of the Eastern Great Lakes and Midwest Biblical Societies 29 (2009): 37-49.

James M. Scott, “Adoption, Sonship,” ed. Gerald F. Hawthorne, Ralph P. Martin, and Daniel G. Reid, Dictionary of Paul and His Letters (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1993), 15–16; John W. Drane, “Sonship, Child, Children,” ed. Ralph P. Martin and Peter H. Davids, Dictionary of the Later New Testament and Its Developments (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1997), 1115-17.

R. Banks, “Church Order and Government”, eds G. F. Hawthorne, R. P. Martin, D. G. Reid, 132.

Hellerman, 126.

Köstenberger, 169.

A.C. Thiselton, The First Epistle to the Corinthians: A Commentary on the Greek Text, (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2000), 512–513.

Scobie, 859.

E.g. Matt N. Williams, Money can’t fix everything the impact of family relationships on poverty (Cambridge: Jubilee Centre, 2020) and P. Parkinson, “The importance of safe, stable, and nurturing families”, Publica (2020) https://publica.org.au/the-importance-of-safe-stable-and-nurturing-families/.

For a recent opinion piece on the importance of extended family see D. Brooks, “The Nuclear Family was a Mistake” The Atlantic Monthly, (03, 2020): 55-69.

On adoption see Gilbert Meilaender, Not by Nature But by Grace: Forming Families Through Adoption. (Notre Dame: Notre Dame University, 2016); R. Moore, Adopted for Life: The Priority of Adoption for Christian Families and Churches. (Wheaton: Crossway, 2015, 2nd ed.Moore 2015

P.W. Marty, “Family as Idol.” Christian Century 137.1 (2020): 3.

The burden of disease measures the contribution a particular condition makes to the total loss of years of life and the total number of years with which people live with disability.

Ayre, J., Lum On, M., Webster, K., Gourley, M., & Moon, L. (Examination of the burden of disease of intimate partner violence against women in 2011: Final report (Sydney: ANROWS. 2016).

See D. Umberson, M.B. Thomeer. “Family Matters: Research on Family Ties and Health, 2010 to 2020.” Journal of Marriage and Family 82.1 (02, 2020): 404-419 for a recent review of literature on the relationship between family life and health which helps to show that “family ties have wide-ranging consequences for health, for better and for worse.”

F.B. Bourg, “Domestic Church: A New Frontier in Ecclesiology.” Horizons 29.1 (2002): 42–63.

The idea and terminology has been used in evangelicalism as well, e.g. P. Beck, “The ‘Little Church’: Raising a Spiritual Family with Jonathan Edwards”, PRJ 2-1 (2010): 342 –353.

See WCF 27:4, C. van Dixhoorn, Westminster Confession 363-4. M. Horton, The Christian Faith (Zondervan, 2013), 793.

Dutch Reformed thought has particularly recognised the distinction of various institutions with the concept of “sphere sovereignty”. See S.P. Kennedy, “Rethinking Consociatio in Althusius’s Politica” Journal of Markets & Morality 22/.2 (2019): 305-316; M. J. Tuininga, “Abraham Kuyper and the Social Order: Principles for Christian Liberalism,” Journal of Markets & Morality 23.2 (2020): 337-361.

Bronwyn Lea, Beyond [Awkward] Side Hugs: Living As Christian Brothers and Sisters in a Sex-Crazed World (Nelson Books, 2020).

D. Schrock “Perspectives on Christ-Centered Family Discipleship” Journal of Discipleship and Family Ministry 4/2 (2014): 104-115, who argues that Jesus call to put him before family is a “key” for Christians to glorify God in their families.

Bavinck 2003, 525–33; G.W. Bromiley, Children of Promise: The Case for Baptizing Infants. (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1979); L.J. Vander Zee, Christ, Baptism and the Lord’s Supper: Recovering the Sacraments for Evangelical Worship. (Grand Rapids: IVP, 2004), 121-34.

On a new covenant view see T.R. Schreiner, S.D. Wright, eds Believer’s Baptism: Sign of the New Covenant in Christ (Nashville: B&H, 2014).

See the review of Puritan literature J.R. Beeke, P.M. Smalley, “Puritans on the Family: Recent Publications” Unio cum Christo 4.2 (Oct 2018): 209-224; J.L. Duncan, III, T.L. Johnson, “A Call to Family Worship”, 317-338, Give praise to God: a vision for reforming worship P.G. Ryken, ed, (Nutley: P&R, 2003); L.A. Powery, “Family Worship.” Ex Auditu 28 (2012): 180–86; B. Howard, “What Works For Us (and Might Work For You) in Family Worship.” The Journal of Discipleship & Family Ministry, 4.2, (Spr 2014): 142–144.

See F Popcorn, “Welcome to 2030: Come Cocoon with Me” June 15, 2020 https://faithpopcorn.com/trendblog/articles/post/welcome-to-2030/.

K.G. Smith, “Family Requirements for Eldership.” Conspectus 1 (March 2006): 26–41.

The phrase miās gynaikas andra is probably best translated “faithful to his wife” as in the NIV. The elder is also required to have “faithful”, that is respectful and obedient children, not necessarily “believing”. Köstenberger, 239-49, S.H.T. Page, “Marital Expectations of Church Leaders in the Pastoral Epistles.” JNTS, 15.50, (Apr. 1993), 105–120.